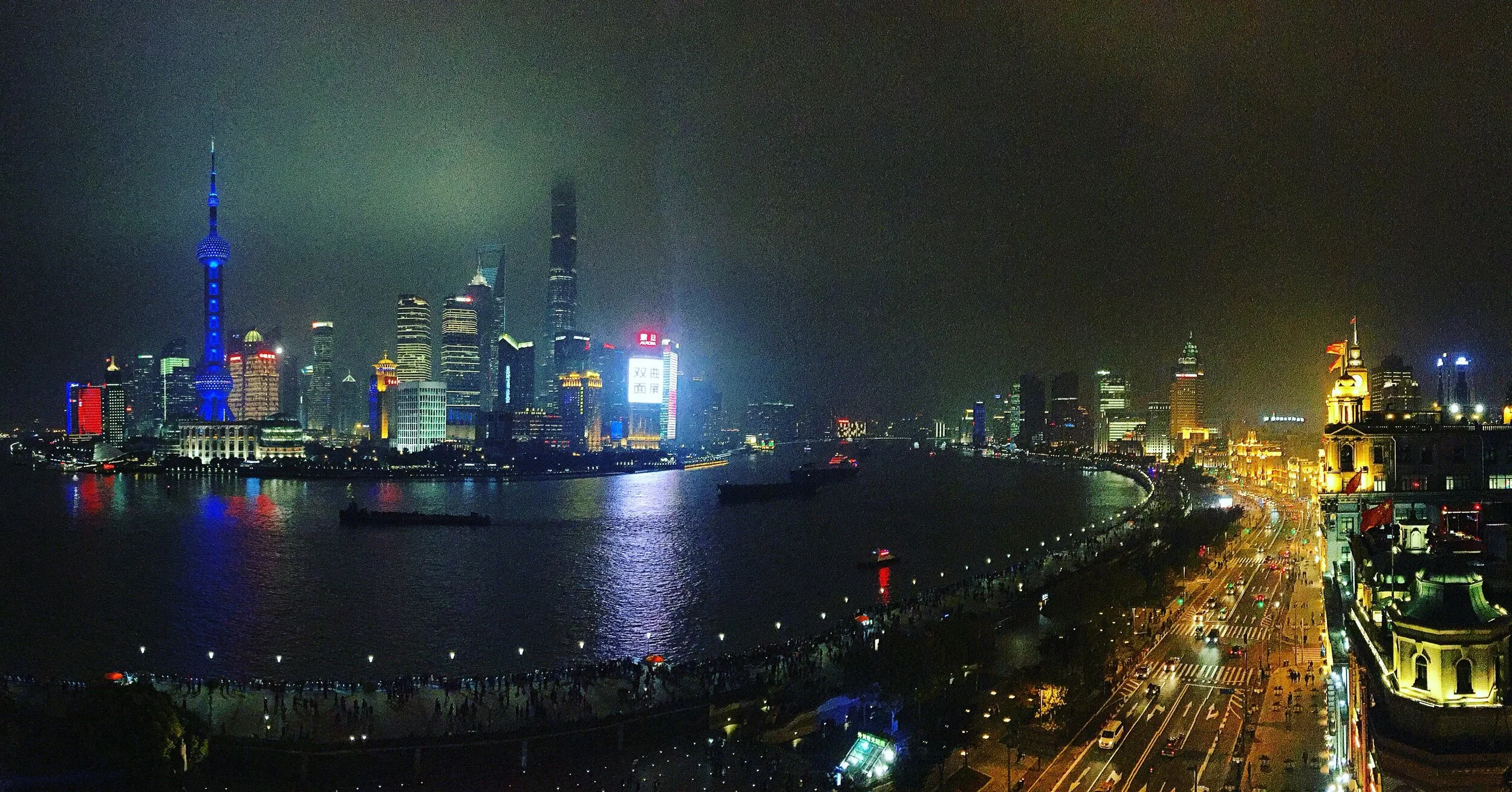

The Shanghai Dream

I have always had a fascination with Shanghai, the dream-like city where East meets West, and old meets the new. My grandfather, Qiusi Dong, translated Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield into Chinese when he lived in Shanghai in the 1930s. For me it’s one of the few places that could bridge China and the West, and where new ideas are born.

Revisiting Shanghai’s Jazz Age

When I arrived here in the soaring August heat, the city’s hottest summer in 140 years, my vision of Shanghai was suddenly hit with a reality check. I had set off in search of the International Literature Talk, part of the tenth Shanghai Book Fair. The talk was to be hosted at Sinan Mansion, situated in a regenerated historical site on Rue Massenet in the centre of the French concession. During Shanghai’s Jazz Age, it was the equivalent of London’s Bloomsbury Square in the 1920s. It housed the city’s movers and shakers, ranging from intellectuals to politicians and industrialists. Less than a century later, it is now home to luxury shops and Hotel Massenet, one of the most expensive boutique hotels in town.

I don’t know why, but I had expected the Literature Saloon to stand apart, unsullied by the commercialism that surrounds it. Instead, the only thing that caught my attention was people enjoying English high tea, courtesy of Whittard of Chelsea and their newly established store in the city. After offering me afternoon tea, the store manager kindly directed me to the end of the villas, where I found the Literature Saloon.

In its third year as part of the Shanghai Book Fair, the Festival had invited 21 Chinese and international authors including Britain’s Geoff Dyer and Italy’s Paolo Giordano. I, however, was there to hear Peng Lun, editor of Shanghai 99 and publisher of the Chinese edition of Granta, host a conversation on literature and the urban experience, between New York-based Irish writer Colum McCann (whose novels Let the Great World Spin, Zoli and short story collection Fishing in a Sloe-black River have all recently been introduced to China), and Shanghai-based novelist Xiaobai, whose Concession will be introduced to an English-speaking audience for the first time by HarperCollins late next year.

The talk had attracted a full house, attended by hundreds of locals. The young audience — many under 20 but mostly under 30 — was fascinated by the New York life described in the novel, and how it contrasts with their strong opinion of cosmopolitan life in China. But they were not just here to listen. The Q&A session drew a level of response that I have not previously seen at a literary event.

“We have all heard of the American dream — a land of opportunity for prosperity and success, the Irish Dream — a land for romantic poets living elsewhere. What about the Chinese dream?” a young girl eagerly asked. “What’s your interpretation of that?” “I feel so ashamed that it’s my first time in Shanghai…” McCann laughed. “I haven’t come across many English translations of books written by the Chinese but I loved it the minute I landed in Shanghai — I didn’t know what to expect, but the sky is blue! For me I think it doesn’t matter whether the dream is American, Irish or Chinese. It’s about telling a story of its people that would engage an audience elsewhere. In literature, story matters — not by what it says directly, but what it allows one to think.”

The audience gave a round of applause to this answer, and the satisfaction on the faces of the younger attendees was plain for all to see. When you come to a place where hundreds and thousands of people queue in 40-degree heat until 10pm to buy books, you get some idea of their thirst for knowledge.

An Age of Anxiety

The Chinese are living in an age of anxiety. Some of the most popular programmes in the book fair were talks promoting books on a healthy lifestyle — a reflection of the pressure brought by an aging population and healthcare reform in modern China. On the one hand this anxiety is conveyed through materialist and pop-culture protagonists, aspiring to the “new fortune dream”. On the other, some of the talks and book signing sessions I went to were attended by a Chinese audience who were earnest in their search for things with real social value and intellectual stimulation.

Shanghai today is still in a golden age, shown literally and metaphorically in the controversial bestseller Tiny Times by Chinese writer Guo Jingming, who, unlike most authors of the previous generation, has no nostalgia of the olden days. His trilogy, which tells a story of four high school girls’ fantastical upper-class life in modern-day Shanghai, has become a hit in China and will be released in North America later in the year. The book signing session of the author-turned-film director resulted in scenes of screaming fans normally associated with a movie premiere.

The rapid cultural shift in values to materialism was unforeseen. Some locals would buy a bag for 3,000 yuan without blinking an eye, but hesitate at the thought of spending 30 yuan on a book. I asked Tian Zhi, an editor at Yilin Press, the prestigious publisher known for introducing international literary classics into Chinese, about the value of publishing in China today: “Post- materialism,” he says, “all I hope is to introduce new ideas to encourage the public to take up social responsibilities, and for China to find something of universal value.”

China is keen to understand the world, much more so than we realise.

In response to popular public demand, the Shanghai Book Fair will be extended to 10 days next year. Jacks Thomas, Director of the London Book Fair, was invited by the Fair to contribute to a book on world book fairs. During my brief encounter here, I tried to interpret the city and its people by piecing together the missing fragments. For me it evokes a delicate truth: China is keen to understand the world, much more so than we realise. This autumn Shanghai will host its first ever International Children’s Book Fair, with two days as a trade fair and the last day open to the public. How many parents will bring their children to queue for books and listen to talks? I don’t know, but I suspect the organisers won’t be disappointed. I hope it will be an opportunity not only to introduce new ideas to China but also a chance to show the world what China has to offer. At least in China, children are the future of the Shanghai dream.

This article was originally published on BookBrunch UK Opinion International